Placebo, Nocebo, and the Mind-Body Connection

The evolving fields of neuroimmunology and nerve stimulation therapy have started to reveal the patchwork of what drives mind over matter

One of the requirements of a senior internal medicine resident, or “R3” as we were called, was to deliver a morning report to the interns. A departing sign-off. The topics ranged from a resident’s past Ph.D. research into the microbiome, to an equally polished stand-up routine riffing on the dubious origins of medical colloquialisms overheard on rounds (the Falstaffian “better part of valor” does not mean what doctors think it means).1

Bound for infectious diseases fellowship at the time, I lectured on the perils of antibiotic overprescription and hints of an impending post-antibiotic era. Later at Johns Hopkins, I worked shifts in the oncology hospital and would marvel at the veritable sea change happening in their field—advances made in targeted cancer therapies, mirroring closely the antibiotic revolution of the century before. At the same time, the number of patients with truly untreatable infections increased year after year of fellowship. Infectious diseases and oncology seem to be trading places.

But before landing on the topic of superbugs and antibiotic resistance, I spent a week deep-diving into the obscure, at the time, field of neuroimmunology. Not focused on the immunology of the brain in situ, but rather the brain and the immune system at large. A co-resident friend of mine with a chronic health condition was going through a life-threatening setback, and as part of my “active-coping” response, I reviewed the literature of nerve stimulation therapy, the conceit being that the brain-immune system interface can be manipulated with therapeutic effect.

A literally off-the-shelf version of this idea is transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for chronic pain.2 The underlying mechanisms of how TENS works are not entirely understood, but theories include pain signal interruption, direct endorphin release, and gate control theory, where electrical stimulation from the TENS unit “closes the gate” on pain signals sent to the brain, prioritizing the sensation of the electrical stimulation over the sensation of pain.

These mechanisms remain intrinsic to the brain and the neurosignaling circuitry, focusing largely on how to modulate or suppress the transmission of pain signals within the nervous system. But a fourth theory, on the periphery, speculates that TENS might in some scenarios stimulate the body to heal outright, addressing the root cause of pain rather than simply masking it. Tissue repair stimulated by the release of chemical signals induced by electrical nerve stimulation has been seen, but inconsistently and inconclusively.

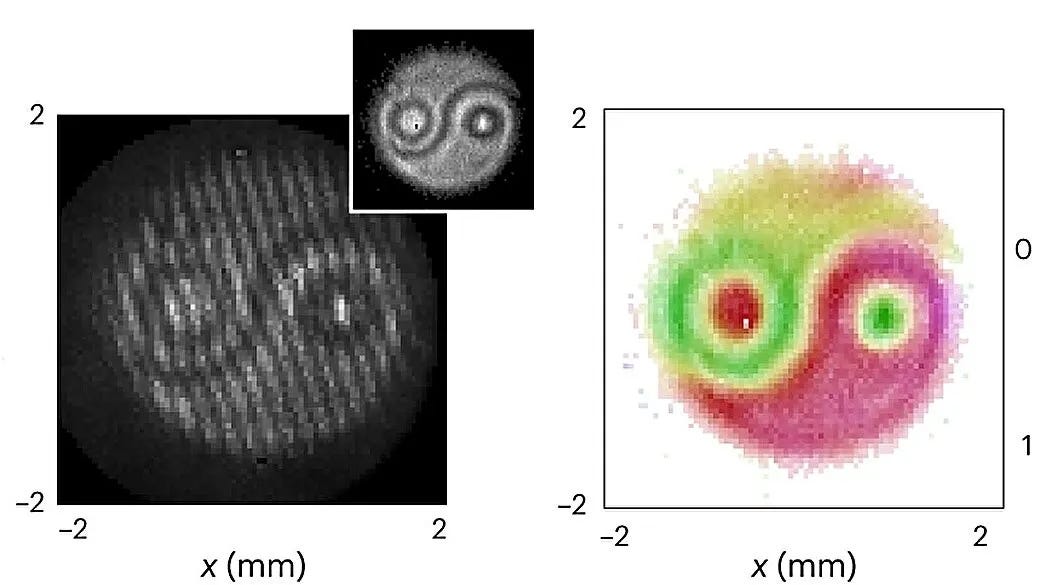

There is more convincing evidence of the neuroimmunological effects of internal nerve stimulation (whereas TENS is external, via the skin). In a study published in Nature of an animal model of sepsis, vagus nerve stimulation reversed some of the sepsis physiology, preventing the development of life-threatening shock. The vagus nerve, descending from the primitive brain and sidling past our diaphragm to deliver its branches to our viscera, provides parasympathetic (subconscious) innervation. Interestingly, it “synapses” with our spleen, a primary immune organ, and modulates splenic activity through what is called the inflammatory reflex. This has led some scientists to ponder how we might one day use our neurological relationship with the immune system to prevent or treat disease.

Decades past, when the doctors who trained me were themselves in training, they could write prescriptions for actual placebo. Ethically fraught, and referred to slyly as “Obecalp”, the non-therapy had its place in the practice of the times. Today, medical ethics have evolved positively away from paternalism toward patient autonomy, while at the same time the science shows that the “placebo effect” is not only real, but has a nontrivial effect size.3

Conversely, there is a “nocebo effect”, too. The dark side to placebo’s light side, “nocebo” refers to a negative outcome that occurs not because of the treatment itself but because of the patient’s negative beliefs or perceptions about the treatment. This can manifest in worsening symptoms or even the creation of new symptoms, all fueled by the power of expectation and belief. The dynamics of both placebo and nocebo effects can confound how we test and prove new treatments, and wrestling with them is necessary not just in assessing treatment efficacy but also in understanding patient psychology and its role in healing.

How much else of medicine is mind over matter? In his collection The Medusa and the Snail, the beloved physician-essayist Lewis Thomas marveled at the ability of warts to be willed away:

The strangest thing about warts is that they tend to go away. Fully grown, nothing in the body has so much the look of toughness and permanence as a wart, and yet, inexplicably and often very abruptly, they come to the end of their lives and vanish without a trace. And they can be made to go away by something that can only be called thinking, or something like thinking. This is a special property of warts which is absolutely astonishing, more of a surprise than cloning or recombinant DNA or endorphin or acupuncture or anything else currently attracting attention in the press. It is one of the great mystifications of science: warts can be ordered off the skin by hypnotic suggestion.

The mind-body connection is evinced daily by the simple act of feeling butterflies in your stomach before an important meeting. Or, in the other direction, by the elation of a runner’s high.

For those of us with long Covid, positive thinking and the positive thoughts of others will not heal us. But there is, at least anecdotally, relief to be found in attempting to ride the neuroplasticity of our brains and rehabilitate-through-resculpting it in meditation, attention training, and other cognitive exercises. On the darker side, the uniquely eerie nature of Covid psychosis underscores just how profoundly neuropathological, and different, this disease is.

The boundary between brain and reality fades the more we learn. Old dichotomies give way to new syntheses. Perhaps like another beloved essayist and humanist, while we seek healing, we must also leave room to not resist suffering and disease:

[Michel de Montaigne] humanized rather than conquered his disease. A mature humanism replaced his youthful Stoic philosophy of detachment and disengagement and provides a worthy model for our own medical humanism.

From Wasserstein in Annals, “Lessons in Medical Humanism: The Case of Montaigne”, linked above.

A phrase attendings and residents deploy in defense of conservative medical decision-making, such as prescribing a treatment or ordering a test when medically unnecessary. Interestingly, Shakespeare was giving voice to Falstaff’s battlefield anti-heroics when he coined the phrase.

It’s worth noting that while TENS units are effective for some people, they do not work for everyone or for all types of pain. Always consult a healthcare provider for a proper diagnosis and treatment plan for pain management.

There is a lot of nuance that qualifies this statement. See for example the Hawthorne effect. Plus, different conditions are differentially prone to placebo.